Ignacio Trujillo, researcher at the IAC, leads the CATGALDF26 project. Using Light Bridges’ infrastructure—home to the world’s largest robotic telescope system—his team is re-observing iconic objects to reveal structures that have remained invisible until today.

Ignacio Trujillo Cabrera is an astrophysicist and Senior Researcher at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), world-renowned for his studies on galaxy evolution and low-surface brightness. His career has focused on understanding the formation of galactic structures and the nature of dark matter. With the CATGALDF26 project, Trujillo returns to the “classics” of astronomy, applying cutting-edge technology to complete the map of the most emblematic galaxies in our sky.

Cutting-edge Science in a Unique Infrastructure

The CATGALDF26 project stands out not only for its scientific ambition but also for the technology that powers it. Observations are carried out from the Teide Observatory using Light Bridges infrastructure, which currently stands as the world’s largest robotic telescope system.

Unlike conventional observing models that depend on direct human operation, the Two-meter Twin Telescope (TTT) and the Transient Survey Telescope (TST) are designed as a fully robotic and synchronized infrastructure. Automation executes the observations, while humans deliver the highest added value: conceiving scientific proposals, interpreting the data, and advancing scientific knowledge.. Featuring two 2-meter and two 80-cm telescopes, the TTT is the first of its kind managed entirely by Artificial Intelligence (AI/ML). This digital architecture optimizes every second of observation, processing hundreds of nightly tasks with a level of precision and efficiency that sets a new standard for public-private collaboration in world-class science.

The CATGALDF26 project focuses on ten historic galaxies, many belonging to the famous Messier catalog. Why turn our gaze back to objects we have known since the 18th century?

It is a fascinating paradox. One would think that the closest galaxies are the best-studied, but they still hold secrets. Historically, in the 20th century, these galaxies were studied using photographic plates: you could see the entire object, but only its brightest parts. Then came modern digital detectors (CCDs). The problem is that, on large telescopes, the sensor is usually much smaller than the galaxy itself.

Does that mean the modern images we see are, in a way, incomplete?

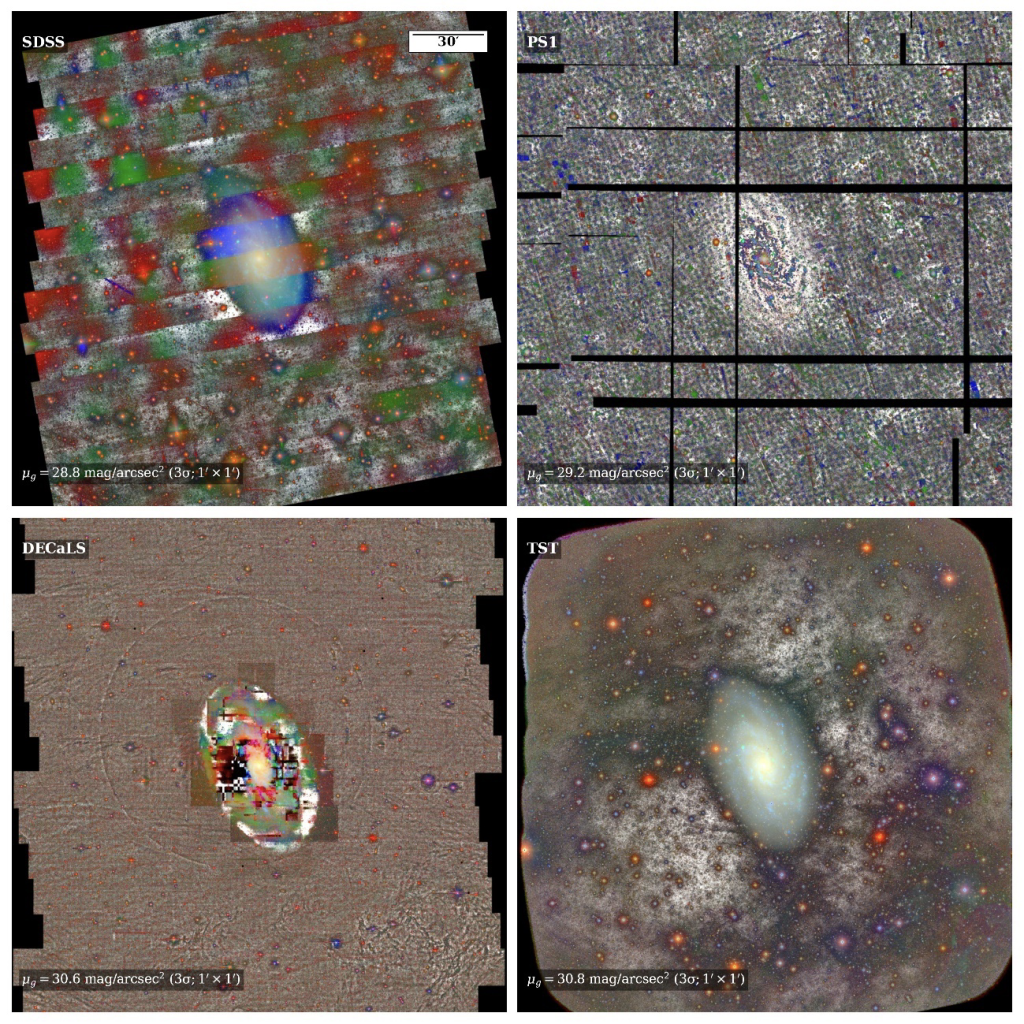

Exactly. Because the detector is smaller than the object, the image becomes fragmented. To cover the entire galaxy, you have to stitch many pieces together, and in that data reduction process, the low-surface brightness structure of the galaxy is broken. What we are doing is recovering a holistic vision. We want to see the galaxy as a whole again, but with a depth a thousand times greater than that of the old photographic plates.

“The revolutionary aspect of Transient Survey Telescope (TST) is the size of its detector and its robotic capability: it allows us to see the entire galaxy without fragmenting it, something that today’s largest telescopes cannot do.”

What role do the next-generation FERVOR/COLORS instruments play in this process?

They are fundamental. While other modern telescopes “destroy” the image by fragmenting it, with Light Bridges’ instruments, the object fits perfectly within the detector. To give you an idea, a galaxy like M33 occupies the size of two full moons in the sky. Thanks to the large area we cover, we can apply techniques that respect the faintest structures. It is an extremely competitive system for understanding the nearby universe.

You talk about detecting “hidden structures.” What have you found by looking at these galaxies with this new level of depth?

We are discovering that galaxies are much larger than we thought. For example, in the galaxy M74, what previously looked like a yellowish-white smudge now reveals a massive blue extension around it. It’s almost double the expected size! This has direct implications for how we understand galaxy formation. Suddenly, what seemed like a simple structure becomes a “nightmare” of wonderful complexity that forces us to rethink the object.

The project selects 10 galaxies for this year. How do you choose which objects to observe?

We chose ten because that is what the necessary exposure time allows—about 40 hours per object to reach these depths, while allowing us to demonstrate the project’s feasibility as we prepare for a long-term European grant.. The advantage of working with a robotic system like Light Bridges’ TTT and TST is the workflow dynamic. The AI optimizes the scheduling and allows us to carry out observations that would be impossible through traditional committees due to the continuous time required.

“In galaxies this close, we can do something unique: resolve their individual stars while simultaneously studying them globally as a whole.”

You mentioned that this work would be much faster with an even larger network of telescopes. Is that the future?

Absolutely. If we had a network of ten telescopes like the TST working together, it would be equivalent to a three-meter telescope, but with a giant field of view. What now takes us months of observation could be done in a single night. It is an efficiency model that Light Bridges has already proven is possible to implement.

After years of studying the most distant and diffuse objects, how does it feel to rediscover the “posters” of lifelong astronomy?

It is exciting. We are moving from a “textbook” image to a much deeper scientific reality. We are seeing the remnants of their formation, their true edges, and their interaction with the environment. We are rewriting the biography of our galactic neighbors because, for the first time, we have the right instrument and management model.